College baseball left a bitter taste in my mouth. I was angry at my body for not holding up, angry at myself for not preparing the way I should have in high school, and angry at some of my coaches for not guiding me in the way I thought a mentor should.

I had some unfinished business with baseball, but at the conclusion of my undergraduate degree, I didn’t think there was a route for me to actually do anything about it.

I grew up in Vermont. People had “real jobs” where I grew up – they were plumbers, craftsmen, construction workers, electricians, teachers. I didn’t even know being a baseball coach was a real profession outside of MLB and the Minors.

I had a weird feeling at the bottom of my stomach that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. But I was sure that building computer models for the Food and Drug Administration did not resolve that feeling.

When I started coaching baseball again, I started to feel better. I was doing the right thing—helping people. I’m sure I was indirectly doing that at the FDA as well, but I couldn’t see it. I would do the work, send it to my boss, she would say good job, and that’s about it. Coaching baseball, I would give a kid a piece of advice, they would do it, and when it worked, their face would light up. It gave me a rush that I just wasn’t getting as a scientist, regardless of whether or not my work was important.

I was hooked; I had to do something in this field, or at least try. I figured that if I started a business and it didn’t work, then I had enough experience on my résumé, where I could just apply to grad school later if my business flopped. Being a business owner could even be a thing that could help me better market myself to a graduate school if I spun it correctly.

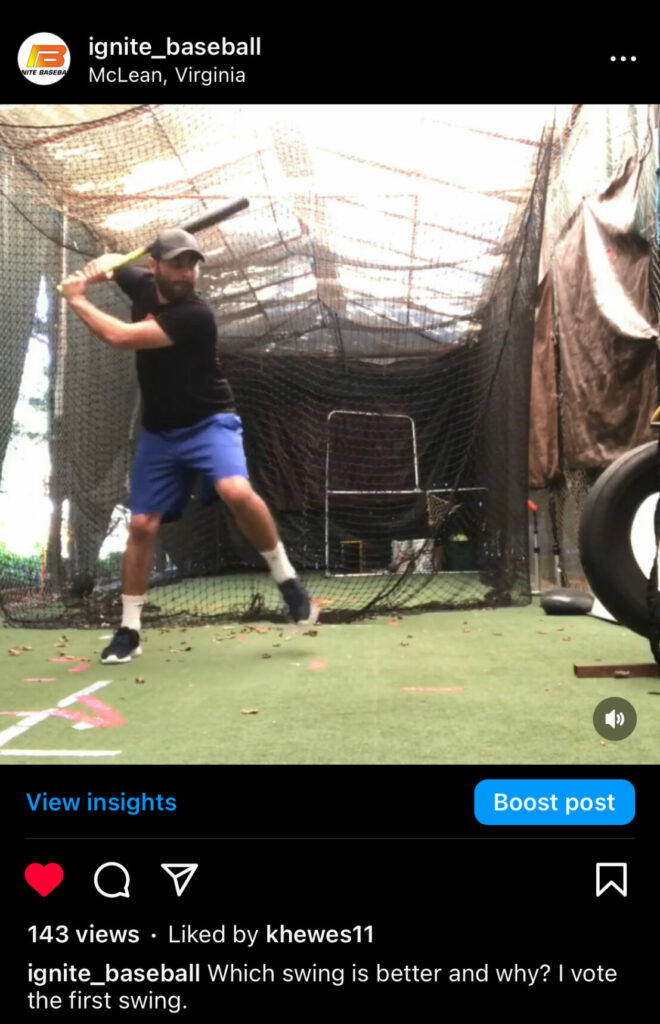

So I quit my job and dove in headfirst, teaching lessons at high schools whenever the cages were not being used, then working out of the backyard. I didn’t know what the heck I was doing, but I was figuring it out.

And I knew that I would be able to get my hands around the best way to do this if I just started doing it. I had some ideas about what I wanted to teach, but nothing was really figured out. What should I teach first? The lower half? Or the upper half? How should I teach the lower half? How should I teach the upper half? I didn’t know.

I knew I had learned a lot of drills, read a fair amount of hitting books, but there wasn’t any playbook that was really laid out yet. I needed to figure out something that would produce results consistently so I could help people best.

After years of trying multiple things and running some A/B tests – basically selecting five or six people to teach the same thing and another five or six people to teach something different, then comparing the results – I wasn’t doing anything crazy scientifically; the data was not rigorous; it was really just the eye test. Were you improving? Or were you not?

I was broke; I couldn’t afford much technology, but I was making it work. Here’s a few pictures over the years.

Things have come a long way since then. Instead of renting cage space or working out of a backyard, we have a facility now. Instead of not knowing what we’re doing, we have a clear process that consistently produces results. Instead of it being just me, we have a team that can execute at a high level.

I’m proud of what we’ve built at Ignite. But most of all, I’m proud of the people we’ve been able to help. Because ultimately, that’s why I started Ignite – I wanted to help as many baseball players as I could. When I see an athlete struggling to figure it out, or frankly, just frustrated with his or her results, I see a younger version of myself, and I want to reach out my hand. That’s what Ignite is trying to do everyday.

Thanks for reading,

Kurt Hewes

Founder & CEO of Ignite Baseball

Director of Player Development Cadets

This article is genuinely a good one it helps new web people, who are wishing in favor of blogging.

Do you have any video of that? I’d want to find out some additional

information.

You reported it fantastically!