In the early stages of my career, I used to think that having an excellent swing was the solution to nearly all problems. While in a lot of cases, it is true that improving the way you move can have a very positive effect on your game production, if you change the upper body at the wrong time or too fast, it can often do more harm than good.

So from an instructional perspective, it’s very important to know when to make specific changes. If we’re smart about what we’re working on and execute those things at the right time, then athletes can move better without experiencing the negative effects of poor game performance.

When it comes to optimizing in-game performance, usually, if you make edits with the way the lower body and the center of the body move, it does not have a dramatic effect on our ability to put the bat on the ball. So, if an athlete is not loading properly or using the center of their body to create an efficient rotation, you can do these things mid-season and be very successful, and the athlete usually will not miss a beat.

But when you start working on their upper body, that’s when problems tend to arise. Hand/eye coordination is really important when it comes to hitting, so if you change the way the hands and arms move, it will have a dramatic effect on our ability to consistently put the bat on the ball. So, we have to ask ourselves the question: Just because something is “wrong” with the upper half, should we change it?

Many times, the answer is no.

People can present many different types of upper body movements and be pretty successful as a hitter. That said, we’ve consistently seen at, and many longtime minor-league players have changed their whole careers by focusing on their bat path. So it would be incorrect to discount the positive effect that focusing on the upper body can have. We don’t want to “fix” an athlete’s upper half that’s crushing the ball in games; that would be insane.

But we do want athletes to be properly equipped, so when they go into the season, they are set up for success. So the questions really become When does your upper body have to be great? What does a great upper body mean? Why do many things work when athletes are younger, and only a few things work when the competition becomes challenging?

OK, let’s start with the first one. When does your upper body have to be great?

We’ve all heard of a hitter having quick hands, and it’s undeniable being able to make quick movements with our hands matters. Especially before the age of 14 or so. When our hands are truly quick we can overcome a lot of things that are not ideal with our upper body. This will work great to a point. Below I’ve listed the average bat speeds of athletes at various levels.

I pulled this from blast motion’s website. https://blastconnect.com/training_center/item/197

* Youth: 40 – 56 mph

* Middle School: 46 – 62 mph

* High School Junior Varsity: 53 – 67 mph

* High School Varsity: 57 – 71 mph

* College: 61 – 73 mph

* Minor League MiLB: 63 – 75 mph

* Professional MLB: 66 – 78 mph

Now let’s look at the same information but I’ll put the average pitch speed at that skill level next to average bat speed.

* Bat Speed Youth: 40 – 56 mph – Pitch Velocity – 50-65 MPH

* Bat Speed Middle School: 46 – 62 mph – Pitch Velocity – 55-75 MPH

* Bat Speed High School Junior Varsity: 53 – 67 mph – Pitch Velocity – 70 – 80 MPH

* Bat Speed High School Varsity: 57 – 71 mph – Pitch Velocity – 80-93 MPH

* Bat Speed College: 61 – 73 mph – Pitch Velocity – 85-95 MPH

* Bat Speed Minor League MiLB: 63 – 75 mph – Pitch Velocity – 90-100 MPH

* Bat Speed Professional MLB: 66 – 78 mph – Pitch Velocity – 95-100+ MPH

Now let’s think about it this way. If you take a look at Bat Speed VS Pitch Velocity you can see something interesting that happens around 8th grade to JV baseball bat speed starts to be greatly outpaced by pitch speed. This is the time where having quick hands doesn’t mean the same thing anymore. Does having quick hands still give you an advantage? Yes, but only if you also have an upper body that is able to get on plane with the pitch with some level of competency.

So what we do at Ignite is train really focus on the upper body when the athlete is in middle school. This way they are prepared when the the pitching velocity begins to outpace bat speed. We find that training the upper body when the athlete is younger than middle school often has diminishing returns. Often kids below the age of 13 do not have enough core control to functionally be aware of their arms in swing this leads to a ton of frustration when attempting to work on upper body patterns. Which often leads kids to not enjoy the sport as much as they did. Early in my career I can’t tell you how many times I tried to work out upper body mechanics with 4th, 5th and 6th graders unsuccessfully. Only to teach the exact same lesson to them when they were middle schoolers to great result.

At a certain point we had to make a decision on when kids can functionally learn this. Middle school and up. There has been less study on developmental journey of movement learning than the developmental journey of a kid learning math. And I won’t pretend that this is a peer reviewed study, but I compare to the upper half in the swing to kid learning algebra. Some very smart/or gifted kids are able to learn it very young and others struggle so much that it makes more sense to introduce it later.

What does a great upper body mean?

At Ignite, the three goals of the swing is something we will always care about.

-

- We want to get our bat into the path of the pitch as fast a possible.

-

- We want to keep our bat in the way of the ball for as long as possible.

-

- We want to hit the ball hard in spots where the defense can’t make a play.

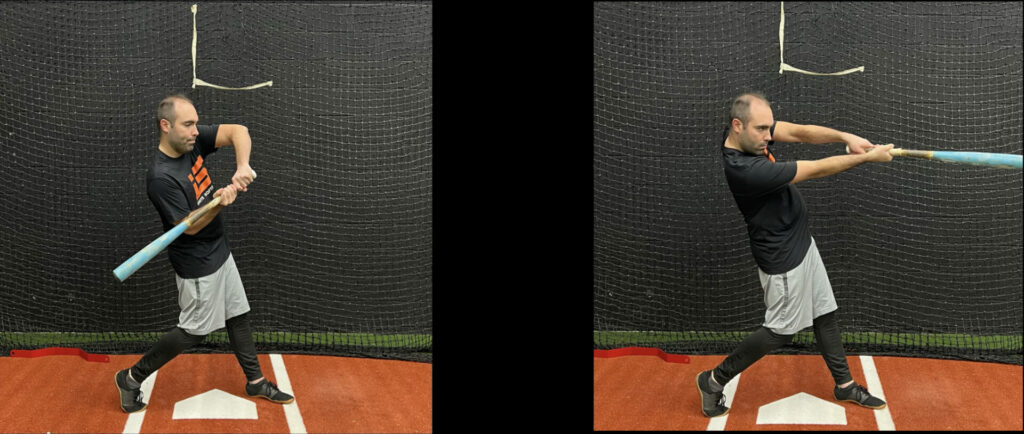

Having a great upper body pattern deals with the first 2 goals. Get in the way fast, stay in the way long. Below we’ll see an upper body pattern that’s functional and allows for adjustments mid-swing.

OK, let’s talk about entering the zone deep with the arms bent.

This concept is pretty controversial. Do I want to hit the ball out front? Generally speaking, yes. However, entering the zone deep allows us to still be functional when we’re late. It can also allow us to design an approach that deals with multiple pitch speeds. If we’re focused on hitting the pitcher’s fastest pitch deep, then with the same swing, we can hit the pitcher’s slower pitches out front. This is generally a good two-strike strategy, but it’s 100% dependent on our ability to enter the zone deep. If we push our hands out directly to the baseball or softball, we won’t be able to do much with the pitch deep in the zone.

OK, arms bent, this is probably the most controversial position. We talked above about having quick hands. This is when having quick hands truly matters, especially when pitching is elite.

If we are able to turn our body with our arms bent at the beginning of our swing, like we see in the picture above on the left, we can then use our extension to deal with the fact that when pitching is ELITE, there’s going to be a lot of late movement and difficult-to-identify pitches that will fool us.

If our arms extend away from our body early in our swing, the only adjustment that we can make to hit the ball is to pull our hands in. This generally leads to foul balls to the pull side.

Why do many things work when athletes are younger, and only a few things work when the competition becomes challenging?

As we discussed before, a young hitter that has quick hands and a solid forward move can basically swing however they want to and be very successful.

As kids get older (middle school and high school), certain things have to be working properly. The athlete has to be consistent with their forward move, they have to rotate relatively well, and their bat needs to be in the zone for a long time. However, the angles that the hitter establishes during their swing aren’t super important at this level.

What do I mean by angles?

The angle that the shoulders, lead forearm, and barrel establish during the swing is very important in the swing the angle of the bat in the swing is called vertical bat angle. This is a pretty important measurement but it’s 100% pitch dependent, and somewhat athlete dependent. It’s not one on those measurements that you could just say “I want your vertical bat angle to be -25 degrees.” We’re looking for a range of roughly -15 degrees on high pitches and sometimes as much of -45 degrees on a low and in pitch. The key with vertical bat angle is whatever angle we establish we want to hold that angle for as long as possible.

The upper body is the most nuanced part of the swing by far. Everybody has their different fields that work for them, many times those feels don’t align with what video shows people doing. There’s also times as I listed above or you just shouldn’t touch the upper body, and it’s taken us years to figure out when those times are. Sometimes an athlete moves their upper body so poorly as a youth player that we have to try and help them on that aspect of the swing. If we don’t help these athletes move better, they just won’t hit the ball at all. Do positive results happen? Yes, It just take a long time and a big commitment on the side of the player/family. So is it a hard and fast rule that we never work on the upper body pattern of a elementary school kid? No, we do work on the upper body young athletes at times but when we do we just don’t stress if they don’t figure it out right away. It will take time, and they likely won’t figure it out until they are middle schoolers so don’t be surprised when it continues to look not great for a while. The key here is having an abundance of patience and accepting what that athlete’s swing is, and not forcing it into what we think it needs to be too early. Hopefully this helps you, your son or your daughter on their path. This was a fun one to write, so I hope that you enjoyed it.

Kurt Hewes

Founder and CEO of Ignite Baseball